D-Day

On D-Day

I was a Pilot Officer on D-Day and had already had over 3 years active experience in the RAF including Day Fighter, Night Fighter, and Special Operations. Three months prior, I had been transferred to the Invasion Force.

The day before the D-Day invasion I was told to go, with my navigator, to RAF Hawkinge (near Dover) where I was told I was flying senior army officers the next day but I wasn’t told where they were going or anything about it at all. We got to Hawkinge and they said to us, “We’re full, we’ve got no room in the mess, we’ll have to put you up in a hotel in Folkestone.” So that’s what they did.

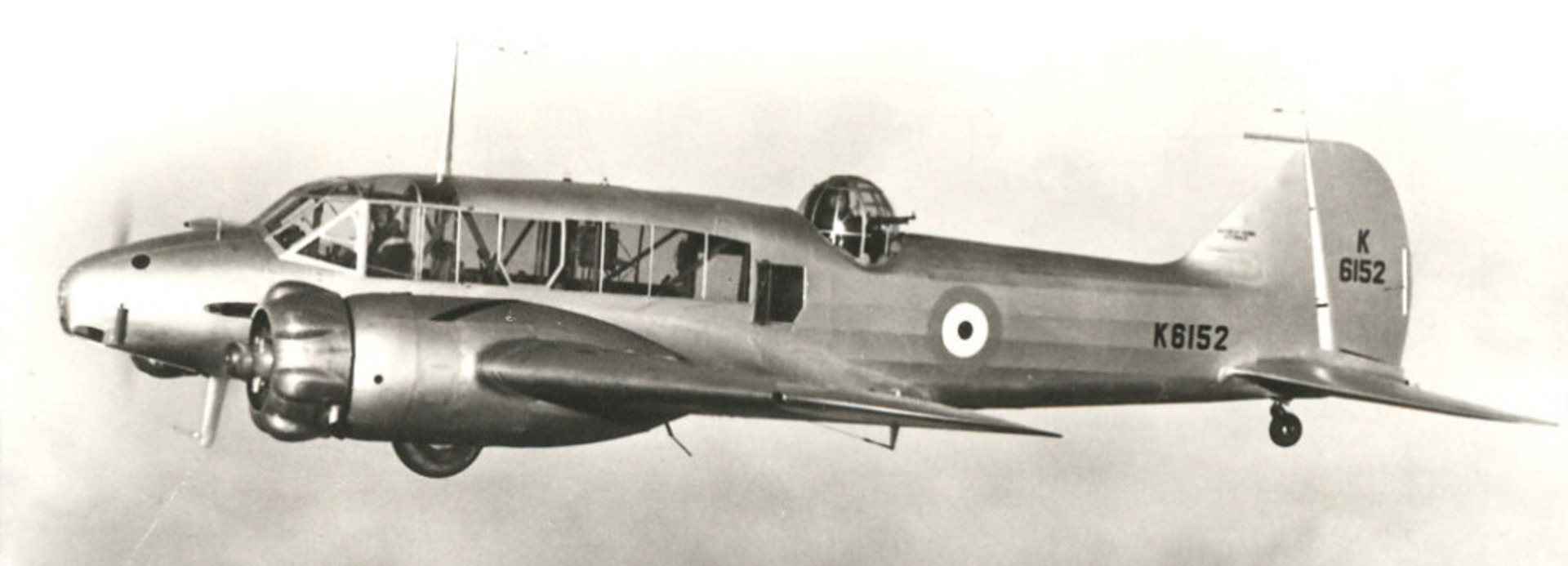

They picked us up early the next morning, I was taken into the Squadron Leader’s office and told it was “likely to be Invasion Day” and we were to fly senior army officers to airfields near strategic points involved in the D-Day operation. (I had been doing this type of operation for months; we called it “SPiT” Senior Personnel in Transport). Within minutes, I was sitting in the pilot’s seat of my Avro Anson plane (known as the “flying greenhouse”) with the engine running. My navigator next to me frantically plotting routes with the information he had just been given. All 6 passenger seats were full and we were waiting for instructions to take off. Only a few minutes later, we heard the airport tannoy system kick in and a passenger, Colonel Barrett, asked me to turn the engine off. I did, and we heard the tannoy announce that the invasion had started and the first landing had just been achieved. No-one spoke in the aircraft. I was then instantly cleared to take off. We spent the rest of the morning flying back and forth along the south coast of England, dropping senior personnel off at each location and collecting more enroute.

Mid-afternoon, I landed at Down Ampney airfield where we saw thousands of army men being launched towards France in Sky Tugs and Gliders. When I said I needed to ring my base, I was simply told, “Sorry, you can’t make or receive phone calls or take off as the airport is “isolated,” you were only allowed in because of who you were bringing”. Once the last Sky Tug took off, I was authorised to continue to SPiT for the rest of the day which we did until late in the evening.

It was a long and tiring day and obvious that a really big, and well organised, invasion had started. I was told to rest the next morning while my plane was tested and repaired, and I then continued to SPiT.

Leading up to D-Day

Prior to D-Day I spent 3 months in the Invasion Force, helping to organise the invasion by doing similar SPiT work, transporting Army, Navy and RAF senior officers and “boffins” throughout the south of England.

Two destinations worthy of mention were Hedley Court (Surrey) and Goodwood House (adj’ the racecourse) where I regularly transported high ranking personnel from all 3 services but these trips were “hush hush” so, the destinations and the personnel simply “did not exist”.

Due to many of the destinations being secret and not near airfields, I often had to land and take off in farmer’s fields, parks, race courses, roads, etc. Landing and taking off from these unusual places meant that the passengers were often “surprised” by my actions. I usually flew them in an Avro Anson which was one of the RAF’s best small planes for short, low speed landings and take-offs. I remember, as we flew between trees and buildings, that many of them gripped the plane seats tightly, pretended to smile and sometimes closed their eyes and, I assume, prayed quietly. As they got out of my plane, they all thanked me profusely and shook my hand with vigour. A person of note was General Crera, commander of the Canadian Army who often had me as his SPiT pilot for the weeks leading up to and following D-Day.

Following D-Day

About four days later I started doing 3 or 4 trips daily to France to drop off army officers. I often used the landing strips that the Royal Engineers were building across the region which made my job so much easier and safer. I continually flew further and further east and south and regularly flew into front line areas. I was constantly at risk of meeting German fighter planes or receiving German ground fire due to my low altitude. Looking back, I see my survival in those days down to good luck and my ability to know how to hide my plane, and passengers, from the Germans (which I’d learnt earlier in the war when I was doing special op’s for the MET office).

Eventually, I moved over to France permanently. A transport team was formed and we took 12 Austers over, flying in formation with a Walrus escort just in case anybody ditched. We had a one hour and 50-minute flight with just two hours’ worth of petrol. Luckily, we all got there safely. Soon we were allowed to take the Ansons over to Normandy where we were based near Bayeux. After the breakthrough at Caen we followed the Canadian army up to St. Omer. The flights got longer and longer as we delivered all the personnel, essential equiptment, and mail, to the various units. We went from St Omer to Gent, from Gent to Antwerp… It wasn’t very pleasant in Antwerp because there were still numerous Doodlebugs and V2’s exploding all over. Then we went to Gilze-Rijen in Holland, a one-time Dutch base which had been taken over by the Germans.

By this time, we’d established daily flights to Brussels, Northolt and Paris and, every so often, to Lasham in Hampshire. We also changed from the Anson 1 to the Anson 5, which was a great relief as we no longer had to wind up the undercarriage by hand. The Anson 5 was a lovely aeroplane.

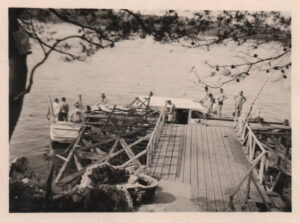

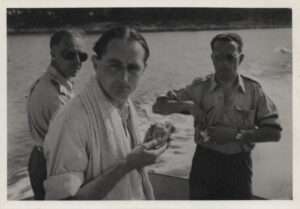

They even established a leave centre in Cannes, so we got the occasional trip down there, landing at Lyon or Dijon to refuel. The second time I went I had to land at Nice and travel to Cannes by road. On the return journey, as we were driving in our Chevrolet, a little Fiat 500 hit us and tipped our car on to its side.

We climbed out and I discovered that two of our passengers were Squadron Leader Medical Officers. One of them asked me if I was alright and I said I was fine. He then said, “I don’t think you are. I think you’re suffering from shock.” I told him I was perfectly fine, but he insisted, with a wink, that I was in shock. It turns out this was the way to get another day in Cannes. One of the officers borrowed a boat and, with some other friends, we headed out for a swim. As we were enjoying ourselves, we heard music coming from a super-boat. A man on the boat shouted down to ask if they could join us. Suddenly someone in our group shouted, “It’s Bob Hope!” and it was. He was visiting the American troops with Jerry Colonna, Frances Langford and Gail Patrick. They joined us in the water, swimming around, which was really quite something. Bob saluted my colleagues and I as he left, which was one of my highlights of the war.

Over the next few months my base continued to follow the front line through Holland and finally into Germany.

On one occasion, I took the Chief of Combined Ops, Brigadier “Lucky” Laycock (who later became the last Governor of Malta) down to Versailles for an urgent meeting with Monty. We got into the aircraft and he asked me where my navigator was. I told him I didn’t have one as there were no spare navigators. To my surprise, he asked if he could sit beside me. I didn’t mind at all and, as I started to wind the undercarriage up, he asked if the navigator would usually do that. When I said they would, he offered to do it. He then assisted me all the way to Brussels and on to Paris. It was dusk by the time we got to Paris and I still had to get back to Celle in Germany. The next day I was very touched to receive a message that he had called to check I’d got back safely. I thought that was very thoughtful, especially for a man of his high rank.

As we forced our way further into Germany, I entered the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp only a few hours after liberation. Hideously thin, freed prisoners were wandering around and mass graves (about 20,000 bodies in each of many huge earth covered mounds) were being uncovered. It was incredibly traumatic for me to experience and one of only 2 times during the entire war that my eyes shed tears.

Over the following days I realised that Germany had effectively lost the war and would have to surrender soon. This cheered me up as many English and Allied people may have died BUT that was about to stop. The whole world would be free and not forced to live under German rule.

I continued to SPiT with key personnel for the rest of the war and my operations usually resulted in me returning to my base with no passengers, so whenever possible I brought back walking and sitting wounded and delivered them to ambulances.

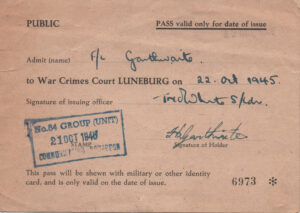

After the war officially ended, I was summoned to the Luneburg war crimes court on 22nd October 1945 to give evidence. This court was within the British occupation zone within Germany and the defendants were 45 former SS personnel from the Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz concentration camps, and I was pleased to do my duty.

I was finally demobbed in Dec’ 45 and I went from Celle to Ostend by train, then boat to Tilbury and bus to Wembley Stadium where we received our de-mob suits and clothes. I then took the train home to West Hartlepool where I was offered 2 months de-mob leave which expired on the 10th Feb’ 46.

Whilst in the RAF, I may have flown 23 different aircraft (including a German one which I “somehow acquired”) for a total of 2231 hours but I’m still afraid of heights to this day. I can’t stand heights. I’m terrified to climb a ladder, but the first flight I took never worried me. As long as the plane is moving, I’m moving and then I’m happy.

Whilst in the RAF, I may have flown 23 different aircraft (including a German one which I “somehow acquired”) for a total of 2231 hours but I’m still afraid of heights to this day. I can’t stand heights. I’m terrified to climb a ladder, but the first flight I took never worried me. As long as the plane is moving, I’m moving and then I’m happy.

My 7 year RAF experience was sad, varied, meaningful, scary and shaped me as a person for the rest of my life. People often ask me why I continued to do some of the very risky things that I did do. What got me out of my bunk and into my cockpit every day was believing 3 facts:

1: If I hadn’t obeyed orders I would have been “court marshalled”.

2: My skills were flying small aircraft to their limits so I was lucky I was in a plane and not in a trench or ship.

3: We all knew that, if we gave in, the world would be dominated and destroyed by Germany.

Many years later, I now realise that:

Fact 1 stopped me having alternative thoughts.

Fact 2 was not always correct, I was just lucky.

Fact 3 was what kept me going … and alive.